Not long after Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Churchill made a phone call to a high-end London tailor, Turnbull & Asser. His request was unusual. Churchill, years earlier, had seen construction workers at his home wear thin garment onesies as practical outfits that were easy to put on. Could Turnbull & Asser tailor some for him?

A few weeks later, their Jermyn Street store delivered several such garments – which came to be known as siren suits for their usefulness during air raid sirens – in a variety of expensive fabrics, including chalk stripes and gray and green velvet. Churchill saved these tailor-made one-piece suits for significant occasions, such as during the Battle of Britain, his visit with Roosevelt in Washington, planning D-Day with Eisenhower, and at the Yalta Conference with Stalin.

They were comfortable, sure, and convenient too. But Churchill was an astute politician who knew how to craft an image. And the siren suits hit all the marks: as outfits worn by construction workers and coal miners, they were relatable to the common man. They showed he was rolling his sleeves up and stepping into the fray. And they communicated that he recognized the gravity of the situation called for a different approach to leadership. The siren suits played an essential role in reinforcing his reputation as a dedicated, relatable, no-bullshit wartime leader.

Churchill wasn’t the first, and certainly not the last politician to recognize the power of clothes in embodying a narrative. With two recent leaders, Zelensky and Netanyahu, pulling a page from the British Bulldog’s scrapbook, I figured there’s something for us to learn by digging into this common but subtle political instrument.

Fashion Trends in Times of Crisis

It is common for leaders to respond to crises by changing their outfits (they do other things too, I guess). In studying how they do it, I noticed three patterns emerge.

Pattern 1: Democratically-elected Leaders Dress Down, Dictators Dress Up

Leaders in democracies prioritize looking relatable and action-oriented during times of crisis. Aside from Churchill, the 20th century saw Lyndon Johnson send casual cowboy vibes from his ranch during the Vietnam War (even if he forgot to take off the gold watch). Reagan showed up in Canadian tuxedos (aka jean on jeans looks) during the recession in 1981, also from his ranch. We saw Jimmy Carter sport nerdy casual during the energy crisis, wearing a deep 70s cardigan instead of his usual suit. Bush’s bomber jacket look after 9/11 was certainly an intentional choice. Germany’s chancellor Gerhardt Schroder was often seen in a raincoat and rubber boots during the country’s devastating 2002 floods. And Tony Blair would wear simple shirts and trousers during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, especially when visiting British troops.

Most elected leaders’ approval ratings start high and decrease over time, especially if nothing major happens and most people tune out. So as leaders who derive their authority from the people, they see crisis as an opportunity to galvanize support and set themselves up well for reelection. It brings the nation’s attention back to them and positions them well to play into the Great Man narrative that is every leader’s dream: that they are history’s hero and this is their time to step up and fight for what’s right — be decisive and stuff. By showing up in ordinary clothes that signal they’re ready step into the fray, they reinforce that image.

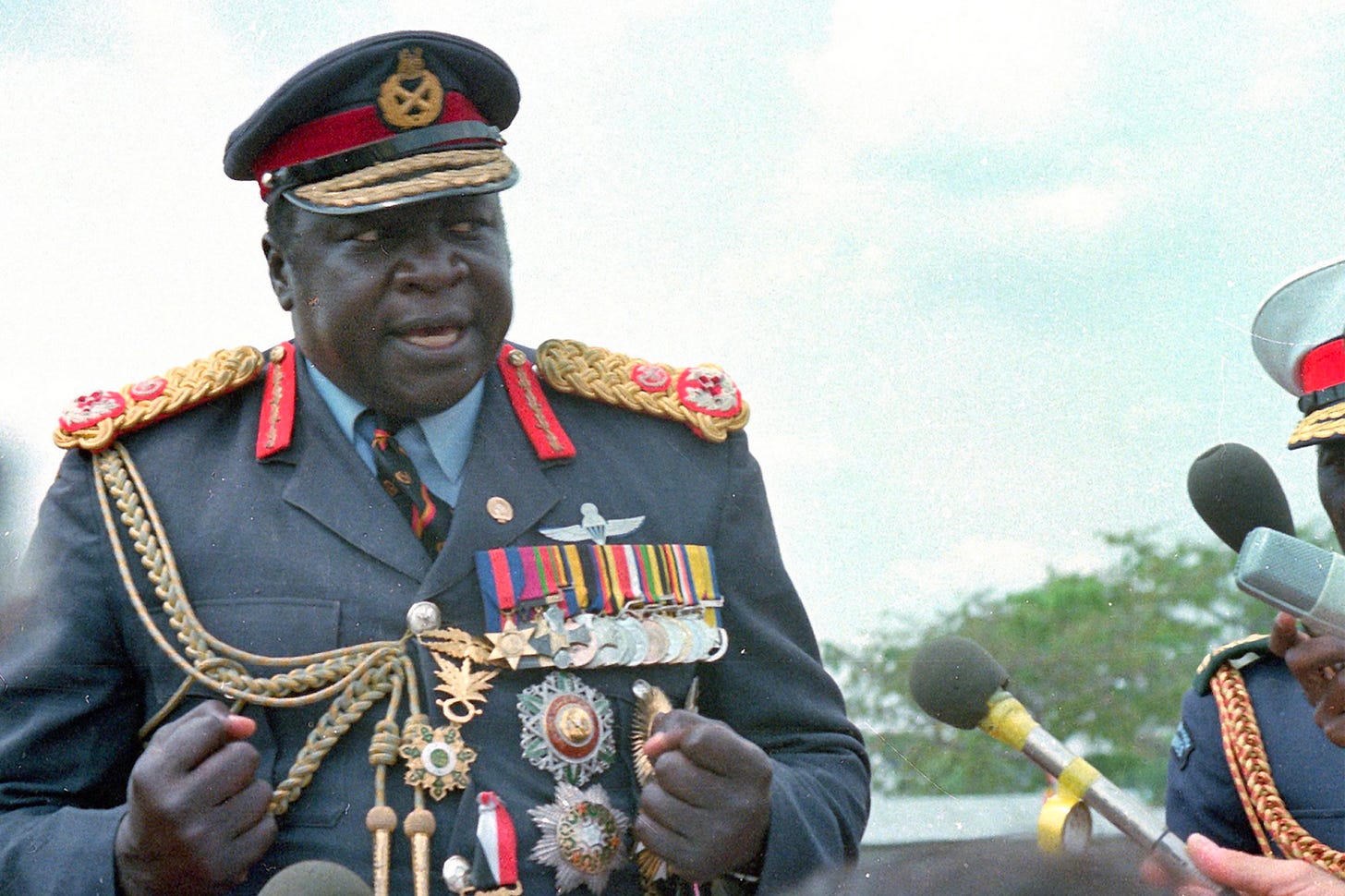

Authoritarian rulers, on the other hand, derive their authority from physical might. Stability is key to their ability to maintain control. Crisis, to them, represents an opening for political enemies and unwanted elements to rear their heads. So it makes sense for them to favor military uniforms, which serve as a reminder of their authority and power, and plays on the strings of patriotism. We saw this with leaders from Stalin to Qaddafi to Idi Amin.

Pattern 2: In Modern Crises, Athleisure Seeps In

Athleisure has been in for a while. The people cannot take another monochrome-branded, sans-serif-fonted, lower-case-stylized yoga-wear brand. But political leaders seem to only now be catching on to the cultural value of wearing clothes that fit for both the farmers’ market and Barry’s Bootcamp.

Ukraine’s Zelensky is perhaps the vanguard of this politico-sartorial movement. Formerly a strict suit-and-tie guy, he is now usually seen in a super comfy-looking Olive-colored sweatshirt with the Ukrainian trident in tiny font, like its from some minimalist Scandinavian shop that has no store sign and plays R&B and whose entire interior consists of four sweatshirts hanging on a wireframe rack.

And if it gets hot, you’ll see him sporting olive green t-shirts that look dri-fit, in case he needs to pop into a pilates sesh in between military briefings. Zelensky, more than anyone, has worn these outfits so consistently they’ve become a distinct part of his image. Together with his unshaven look, he is sending a message that balances authority with approachability, and the green-ness and military fatigue style of his outfits serve as a visual reminder of the ongoing war.

Zelensky is far from the only modern leader veering into super casual clothes, though. COVID, in particular, seems to have brought the boys (and girls) to the athleisure yard. We saw casual sneakers sneak their way into the Oval Office (and generate NYT headlines). We saw Justin Trudaeu address Canadians during COVID peaks wearing sporty, casual clothes. We saw New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern livestream from her home in what looked like a running sweater.

This trend is hardly surprising. Fashion has been on a casualization kick for years. And as Gen Z gains political power and millennials become the largest voting generation, savvy political leaders understand the importance of appealing to them. This is especially true for younger leaders who see the importance of securing the young vote early for their long term career (despite lower voter turnouts in that demographic).

Pattern 3: The Extent of The Transformation is Proportionate to the Scale of the Conflict

The bigger the conflict, the more extreme the transformation. Zelensky, deep in war mode, has changed everything about his outfit. Together with his sweater and t-shirt looks, he is also usually seen in cargo pants and military boots. This is a far cry from the former comedian’s sharply tailored suit-and-tie looks, and has not changed — and likely will not change — until some semblance of peace comes, or his presidency ends.

Netanyahu is similar. Since the Hamas attack, the Israeli premier has worn almost nothing but black shirts (he wears pants too, it’d be weird otherwise). Netanyahu understands the power of fashion as a political tool — his black shirt serves as a reminder of the October 7 tragedy for a world that is quick to forget what kicked off the current conflict. It communicates urgency, and that he is in the man for the job. And lastly, for a political leader often accused of being aloof, it also exudes an everyman quality while avoiding the t-shirt looks that came to characterize the leaders of the opposition movement against him.

By contrast, small crises lead to smaller adjustments. In the US, the 21st century playbook for one-off disasters is to shed the tie and put on a windbreaker for a grizzled, I mean-business-and-I-am-willing-to-stand-in-the-rain look. But the white shirt stays on, and the pants do too, like a quick-change artist who needs to ladle out soup for flood victims at 4 but be ready for a fundraiser at 7.

Bush, of course, bucks the trend, opting for a more fashionable (and comfortable) crisis outfit:

Kidding. I just needed an excuse to use that photo.

But anyways, it’s fascinating to dig into how political leaders use subtle cues to communicate a message or craft their image. It’s all conjecture, of course, but the patterns across cultures, countries, crises feel too large to be coincidental.

Studying this reminds us that we think in stories and that there’s much more to stories than words. It is useful to look to politicians — professional storytellers that they are — to learn how narratives are shaped in other ways. The nice thing about them, too, is that they are pretty intentional about the story they want to tell.

It makes one wonder: how do the micro-decisions we make reinforce a story we have about ourselves? What is that story anyways? And is it aligned with who we are today or who we want to be?

Or you could just wear a jean jacket and call it a day, I guess.

About Me and My Substack: my name is Gil. I work in healthcare tech and love to write, do karate, and ride around New York on a little black skateboard.

I write optimistic takes on things we usually worry about like social media, climate change, and mental health. I also like to analyze trends in human behavior and learn from them, like the rise and fall of ringtones, and what rap can teach us about foreign cultures.