In the 2020s, Caring About Things Will Go Mainstream

And when consumers care, capitalism does too

Businesses create stuff. In the process of creating the stuff they intend to offer, they also create a sweet medley of things that are decidedly less good. The list here is long, and we’ve heard it before, even if we’d rather pretend we haven’t.

The negative externalities businesses create are inputs into what feels like a pretty depressing state of affairs. The climate crisis is reaching intimidating, unprecedented heights (did someone say half a billion animals died in the Australia fire?!), millions of people suffer daily from environmental health risks around the world, mental health issues are driving a steady uptick in suicide rates, obesity is on the rise, inhumane working conditions have been normalized for a nontrivial portion of the population… and so on.

It’s clear that something’s got to give.

And I am optimistic that it will.

I am optimistic because we are seeing the beginning of a shift from enterprises scrambling to avoid responsibility for these externalities to a new class of global business leaders seeking to actively identify and attenuate them.

Now listen.

This isn’t some post-materialist pipedream. The capitalist class has not become altruistic overnight after a period of rough but necessary soul-searching and a tub of Ben & Jerry’s. It’s that changes in consumer consciousness, led by technological advances, increased levels of transparency, and demographic shifts have shown forward-thinking business leaders that ‘doing well by doing good’ makes economic — not just moral — sense.

With today’s value-driven business leaders as its early adopters, a vital, sustainable materialism began to emerge in the 2010s. In the 2020s this new materialism will cross the chasm, going beyond the innovators & early adopters and towards the early majority.

Values, They Are A-changing

In the 2020s, millennials will come into their own as society’s corporate and political leaders.

Here’s what we know about the shifting values of tomorrow’s future leaders:

1. We’re increasingly skeptical of traditional businesses

Deloitte’s 2019 Millennial Survey found that Millennials share a

"growing view that businesses focus on their own agendas rather than considering wider society — 76 percent agree with that sentiment — and that they have no ambition beyond wanting to make money (64 percent agree). It also is likely influenced by a continuing misalignment between millennials’ priorities and what they perceived to be business’s purpose.”

2. We believe businesses are responsible for employee wellbeing

The majority of us (73%) believe that employers are responsible for managing or reducing workplace stress.

A third of us believe that enhancing employee livelihood is a top priority for employers, while only 16 percent feel businesses currently do so. And that’s a pretty high bar to hold companies to.

3. Millennials expect companies to take a principled stance on social issues

More than a quarter of millennials chose not to purchase from an organization because of its stance on a political issue, and 29 percent did the same based on the comments or behavior of a company leader, according to Deloitte’s survey.

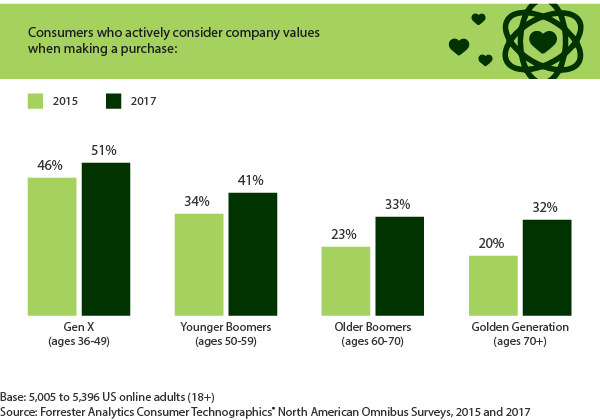

Not only that, but this expectation is more pronounced among millennials than any other age group. In a different in-depth survey, Seven in 10 US millennials said they actively consider company values when making a purchase compared to 52% of all US adults.

4. Our concern for the environment is driving our economic behavior

Driven, perhaps, by the undeniable urgency of the climate crisis, millennials, more than any other age group, are “highly worried about global warming, think it will pose a serious threat in their lifetime, believe it’s the result of human activity, and think news reports about it are accurate or underestimate the problem,” according to a recent Gallup poll.

Explicitly identifying society’s role in the climate crisis, I believe, underlies some of the key trends here. A recent study by Nielsen, for instance, showed that 73% of millennials are willing to pay extra for products that are sustainable.

To quote one study participant:

In other words, I’m willing to spend more (a lot more, in fact) to know that what I’m spending my money on is actually good for the earth and the people on it.

This sounds normal now, but in the broader scope of history, it is a relatively new perspective that flies in the face of the Rational Behavior theory much of modern economics is based. We need only look as far back as the twentieth century to remember that a product’s supply chain was not something consumers worried much about. But we certainly do now.

And It’s Not Just Millennials

I am a millennial and I realize that the world does not revolve around us (allegedly). So it’s encouraging to see this trend cross generational boundaries.

The data shows that Gen Z’s are very much on the same page, which is particularly invigorating given they’ll be the ones taking our spots when we retire to ride our own mopeds around Florida.

A 2017 study on values and attitudes found that Gen Z, which already account for 40 percent of all consumer purchases globally, is the generation most likely to believe that companies should address urgent social and environmental issues: a whopping 94 percent of those surveyed said so (even higher than the 87 percent of millennials).

But that’s only part of the story. We see these value shifts happening across the board. So while it’s true that 70% of millennials care about the source of the ingredients in the supply chain, its telling that half of GenXers and baby boomers do too.

And the best part: we can see an improvement across every generation even over just a two-year period in the 2010s. In fact, 2017 was the first time in history a majority of Gen Xers actively considered company values when making purchase decisions.

Is This Really Unique?

Consumers have demanded change and ethical values from corporations many times before.

So is this really different?

Yes, I believe so. Here’s why:

1. The digital age comes with unprecedented access to information

We, the digitally connected We, have access to a steady stream of information that previously companies were able to shut out from the outside world — whether that’s damning internal memos (Google), recordings of CEOs berating people for making poor life decisions (Uber) or minutes from high-level meetings (Facebook). Hell, when I was at Uber, New York Times reporter Mike Isaac basically live-tweeted our confidential weekly Q&A sessions by getting access to the streams set up for employees around the world. I literally used his feed to catch-up on what I missed.

This is a historically unique vantage point, for the first time allowing us to see past the posturing, the ‘commitment to our values’, the newly-announced CSR departments that made up the corporate playbook for responding to accusations of environmental or ethical neglect in the past.

2. It’s easier than ever to organize mass movements

Having lived and worked through the global #DeleteUber campaign, I remain in awe of the internet’s unique ability to bring people together behind a common objective.

These forces, once unleashed, are hard to control — and can certainly be misguided. But there’s no denying that they have forced organizational leaders to become increasingly mindful of the potential for stakeholders to foment seismic movements that reach far into the customer base to make real damage to the bottom line.

3. This isn’t just youthful idealism

As we saw in the previous section, the shift in values goes far beyond the youthful stereotype of an idealistic liberal who turns cynical over the years.

4. Companies are beginning to fight regulators for what’s right

In the 1980s, when Reagan implemented a variety of regressive environmental policies, corporate America embraced them with open arms. This time, large companies are fighting on the side of sustainability, even against their own short-term self-interest. Patagonia, for instance, announced their plan to give $10 million, the full refund from a federal tax cut they called “irresponsible,” to fight for environmental causes threatened by the tax cut itself.

And whether companies do it because they’re afraid to lose customers or for authentic ethical reasons is exactly the point — what’s unique is that companies don’t have to be bastions of morality to do what’s right, but simply have good business sense.

As the Stanford Social Innovation Review put it:

"Some of the backlash this time will come from businesses that are leading on greenhouse gas reductions and not fighting government-led environmental policies, as they did in the 1980s. Indeed, recent surveys show that 85 percent of business executives believe that climate change is real (well above the national average of 64 percent), and many see the associated market risks and benefits."

What does this mean in practice?

It means businesses are facing mounting financial, societal and internal pressure to behave in accordance with ethical and environmental principles.

Mounting financial pressure

The financial case is pretty clear.

A paper published by the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences sampled 28,578 firm-years, with each firm assessed on their performance in “community, diversity, employee relations, environment, product, and human rights attributes.” Its findings show an undeniable correlation between companies choosing to engage in corporate social responsibility (CSR) with higher profit margins and valuations.

We see this time and again. Companies that make Ethisphere’s World’s Most Ethical Companies list consistently outperform the S&P 500 (chart below). A composite index of JUST Capital’s 2016 rankings of ethical companies consistently outperformed the Russell 1000 on a 10-year basis.

There are a variety of possible underlying factors: companies that act with integrity have lower long-term customer retention costs; it’s easier to attract top talent; voluntary employee churn is lower; there are fewer costs associated with lawsuits and fines.

But even without isolating the specific causes, progressive business leaders are recognizing the implications of this fundamental truth. A recent survey of CEOs found 90% believe sustainability is important to their companies’ business success. Goldman just announced they will not take any companies with non-diverse boards public, explicitly citing data that companies with diverse boards perform better financially.

Beyond profitability, a slew of companies are realizing that responsible operations are simply paramount to their ability to exist in the future — not just the right thing to do. Nestlé, Coca-Cola, Cargill, and General Mills, for instance, have made substantial investments in the environmental sustainability of their operations in the face of threats to their value chain due to the decreased availability of clean water and the fallout from climate change-related events.

Mounting internal pressure

By 2025, Millennials and Gen Z will make up more than 75% of the workforce. These are the same groups that cited “seeking out employment at companies that demonstrate a commitment to responsibility” as a top priority. A 2016 study showed that employees — particularly millennials — increasingly expect their employers to share their values, something that was not a serious consideration for most employees until relatively recently.

These attitudes manifest in a sharp rise in employee activism, forcing even the most apathetic CEOs to seriously consider workers’ opinions when making major corporate decisions.

Whether it’s McKinsey employees pressuring management to stop working with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Nike removing top execs accused of sexual harassment in response to a revolt by a group of female employees or Google cancelling military contracts in response to large-scale walk-outs and sit-ins, today’s level of employee activism (at least in its current form) is almost without precedence in history.

And again, the promising insight here is that millennials are most likely to be employee activists (by a large margin too: 48% to Gen X’s 33%). In early May, Ron Williams, the former CEO of Aetna, reacted to employees who were campaigning against their companies: “I can’t imagine that happening 20 years ago”.

As millennials and Gen Z grow as a portion of the workforce, employers of the 2020s will feel more, not less, responsible for making business decisions that align with the values of their employees.

Crossing the chasm

Crossing the chasm is a framework used to describe how a product or concept ‘goes mainstream’. This, according to Geoffrey Moore’s classic formulation, takes place when a product crosses the gap between the Early Market (innovators, early adopters) and the Mainstream Market.

On this chart, each consecutive audience is a little harder to crack. Whereas Innovators are thought leaders in their communities who are willing to try new things, take risks, pay a premium for first dibs and have relatively low expectations of product/concept fidelity, the Early Majority have high quality expectations and demand a competitive offering.

Conquering the Early Majority after having won over the Early Adopters is exponentially harder than moving from the Innovators to the Early Adopters, and represents mainstream-ization of a product or concept.

Once there, it doesn’t mean a product or idea won’t fail but it means it has proven to be valuable enough to a heterogenous and demanding audience, and therefore is better positioned to have some longevity.

In the 2010s, conscious corporatism moved from the Innovators to the Early Adopters. In the 2020s, it will conquer the Early Majority too.

The Innovators

The Innovators are the social-purpose ‘natives’, companies founded with it in their DNA and who’ve become emblematic for the movement writ large.

Patagonia is the poster child here. They commit 1% of sales every year to environmental purposes, give employees paid time-off to volunteer, ask customers to “buy only what they need and repair it when it breaks”, and actively lobby in favor of social causes (like the Public Lands campaign in headline image). Unsurprisingly, perhaps, their mission statement is “we’re in business to save the planet”.

At their best, these innovators help promote new models of both production and consumption.

Seventh Generation follows a strict product scorecard which grades its materials on greenhouse gas emissions, production efficiency, use of recycled materials, toxicity, among others. The scorecard set the gold standards for their industry more broadly.

In direct opposition to overconsumption, REI, the outdoor lifestyle retailer, closes its 149 stores every Black Friday as part of its “#OptOutside” program. The campaign was so impactful that a bunch of other companies followed suit, including Subaru, Google and Meetup, as well as other outdoor brands like Burton and Yeti.

The Early Adopters

While a small number of companies integrated social purpose from birth, many added it to their values and practices in the 2010s. These ‘social purpose immigrants’, as HBR refers to them, recognized the economic importance of competing not just on functionality, but on corporate citizenship as well. In my eyes, these are the Early Adopters.

The list here is long (and that’s kind of my point), but just to name a few:

P&G, not exactly known for its history of civic activism, has started a campaign to narrow the pay gap with men and to that end, among other things, donated a cool half a millie to the U.S. women’s soccer team; they’re also behind Always’ Like a Girl campaign to champion girl’s confidence, Pantene’s Strong is Beautiful which celebrated and empowered diversity and Gillette’s We Believe campaign which (though controversial) promoted self-acceptance by redefining what it means to be a man

Several big box retailers, including Dick’s Sporting Goods, Kroger and Walmart responded to mass shootings by restricting their sales of guns (Dick’s going as far as destroying $5m worth of guns in their inventory)

In response to some not-hugely-compassionate immigration policies implemented by Trump, American, United and Frontier Airlines refused to knowingly fly children separated from their parents at the border

To curb plastic pollution, Adidas began manufacturing shoes made out of ocean plastic. Demand for the 5 million pairs they produced in 2018 was so high, Adidas more than doubled their production to 11 million pairs in 2019.

Horizontal and vertical change

These changes aren’t simply limited to a handful of cases of large corporations who can afford to make the sacrifices perceived to be associated with running a business with integrity. Both horizontally and vertically, the 2010s marked the beginnings of a shift in good corporate citizenship toward the mainstream.

Over 13,000 companies worldwide have signed the UN’s Global Compact, which sets standards for members “to align strategies and operations with universal principles on human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption, and take actions that advance societal goals.”

Deloitte’s 2019 Global Human Capital Trends report showed that

44 percent of business and HR leaders said social enterprise issues are more important to their organizations than they were three years ago, and 56 percent expect them to be even more important three years from now.

Another survey by Deloitte served to a range of C-level execs found that “73 percent said their organizations had changed or developed products or services in the past year to generate positive societal impact”.

The vast majority of S&P companies (86%) in 2018 voluntarily released sustainability reports, a huge jump from the 20% that did so a mere seven years prior. Along similar lines, the number of certified B Corps — companies that meet rigorous ethical, social and environmental standards — has skyrocketed over the last decade.

These are some major changes.

Industry-wide transformations have begun the shift from niche to mainstream too.

The Electric Vehicle industry is one example emblematic of many. In its latest form (EVs have actually been around since the 1800s), Tesla’s Roadster was the harbinger of the EV revolution in 2008, targeting a slightly-eccentric, tech-y, mega rich audience. In the 2010s, practically every single auto manufacturer has released its own EV in an effort to catch up to the ‘new normal.

Based on what we’ve seen in the last decade, we’re well positioned for conscious capitalism to go mainstream in the 2020s.

Where are the policy-makers?

Data shows that today’s younger generations look to regulatory bodies less and less for solutions to societal and environmental issues. Almost three quarters of millennials said in a recent survey that political leaders are failing to have a positive impact on the world, and only about half of respondents believe “leaders of their current governments are committed to helping improve society or behave in an ethical manner”.

In this vacuum of trust, it seems consumers have begun to realize the power of their own wallet in affecting change.

So while governments will certainly play a role over the coming years, there’s no stakeholder better equipped to push through fundamental change like businesses responding to an increasingly empowered consumer.

And the truth is, that’s a good thing.

In today’s market-led world, businesses are responsible for arranging the world around us: our houses, food, cars, experiences and so on. That means that, although enterprises aren’t solely responsible for transforming society, they do have the tools, resources and global reach to generate the solutions we need at the scale and speed we need them — in the way few governments do.

Is it sure to happen? No.

But I’m optimistic.

If you like this kinda stuff… leave your email below and I’ll email you once a month with casual, meme-filled takes on serious issues.