The Fascinating World of Bootleg Soviet Music

And how it set the stage for Russia to become a global piracy powerhouse

As the child of Soviet immigrant parents, I grew up listening to a lot of angry-sounding men yelling things to the strums of a 7-string guitar. These men, with names like Vysotsky and Galich, were heroic figures in Soviet lore. In the face of strict state censorship, these singer-songwriters built a national following and played a pivotal role in the politicization of an entire generation.

They did this thanks to an intricate underground network distributing pirated music. This same network ripped right through the Iron Curtain, bringing to the Soviet people banned Western music, and with it the liberal and consumerist values it espoused.

Today we’ll dig in to the history of Soviet music piracy, why it became so common, and how Russia became its global headquarters after the socialist empire’s collapse.

The History of Music Piracy in the Soviet Union

Music Piracy wasn’t technically born in the USSR, but it moved there at a young age. Already in the 1910s Russians bootlegged Opera arias on gramophone records, which I guess is a crime but feels like stealing math books from the library. Piracy started actually gaining steam in the 1930s, when the young socialist republic began to suppress foreign influences like Jazz in favor of music glorifying the Revolution. Which, let’s be honest, no one really wanted to hear. But Stalin was also unleashing his Great Terror right around that time, and given any misstep could get you and your family on a train to Siberia, the budding industry remained pretty small.

It took the old dictator a while to die, but when he did in 1953, music piracy began to take off in earnest. The transition from Stalin to Khruschev was a transition from a complete ban on Western media to a (very) selective filtering. Jazz was finally allowed to emerge from the underground, with the records of Dave Brubeck, Louis Armstrong and Bing Crosby circulating openly.

The peek behind the curtain piqued the interest of Soviet youth. It helped that the odds of being executed for smuggling Western media weren’t as high, enabling more Western music to make its way in. Foreign relatives would bring in vinyls as did enterprising tourists, sailors and diplomats. Certain radio stations, like the BBC, would also intentionally send their radio waves past the Iron Curtain. Soviet youth thus discovered the twisting, the shouting and the liberation of Elvis and Little Richard, of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

How the Soviets Used X-Rays to Pirate Music

Driven by the hunger for authentic connection that music offered, and the fascination with the new world it exposed, illicit Western music became a national phenomenon in the USSR. But distribution was a challenge. Resin, which was used to make records, was in short supply and large flat vinyls were hard to smuggle and move around.

There were plenty of X-rays, though, which were thick and durable enough to scratch grooves into. Soviet aficionados figured out they could bribe hospital staff to get ahold of X-rays and use manicure scissors to cut them into a crude circle, burning a hole using cigarettes to complete the vinyl. They made copies by rigging one gramophone to another with a recording stylus and worked in secret, one record at a time. Author Anya von Bremzen put it lyrically: “You’d have Elvis on the lungs, Duke Ellington on Aunt Masha’s brain scan — forbidden Western music captured on the interiors of Soviet citizens.”

These X-ray records were easy to roll up and smuggle in bags and coat sleeves. People bought them from dealers lurking in dark corners, 50 rolled up in each sleeve. Granted, the sound quality sucked, but it was a small price to pay for access to unbridled joy with a dose of rebellion.

X-ray records took off like wildfire. Underground networks of producers and distributors emerged in every major Soviet city. Bootleggers earned celebrity status which they enjoyed both in and out of jail. It became so popular that Soviet authorities legislated against them and began major crackdowns.

But the genie could not be put back in the bottle. In the 60s, music piracy began to shift towards cassette tapes and reel-to-reel recordings. These were easier to duplicate and distribute, and offered better sound quality. By the 70s and 80s, pirated cassette tapes were often sold openly markets. The Soviet authorities recognized that their efforts to ban “un-Soviet” Western media were failing, and instead tried licensing censored versions of Western songs which, to the surprise of no one, never really took off.

How Singing Poets Supercharged Soviet Piracy

It wasn’t only Western music that was being pirated, though. With the 60s came the rise of the Bards, Soviet poet-storytellers who sang their words to the sound of a 7-string guitar, and whose music was a key pillar of Soviet piracy.

Their music dealt with topics that were prohibidado, like freedom and oppression. They painted pictures of what real life in the Soviet Union was like — of long lines, of alcoholism, of domestic abuse. Officially, their music was banned. They couldn’t formally tour. They were barred from TV and radio stations. They were not allowed in the country’s few professional recording studios. And yet, in practice, they became household names across the USSR and the anchor of a growing underground movement.

Because they couldn’t openly record their music, they played to rolling tape recorders in friends’ apartments and small rural venues. Like the X-ray records, the recorded sound was terrible but for different reasons. The tapes were bursting with sounds of cars passing by, babies crying, microphones being passed around, footsteps, furniture creaking. But I love this about these recordings: it adds a “living” quality to the sound, and a conspiratorial sense of audience participation. One observer recalled: “requests, repartee with the singer, warm or bitter laughter, pregnant silence at the conclusion of a particularly telling song followed by a bustle of relieved tension-breaking movement and murmuring”.

It reflected and reinforced the rise of a counterculture movement that saw the regime for what it was and wanted to laugh and cry about it. The tapes from these recordings became the artists’ de-facto albums, and were exchanged for goods that were hard to get or simply distributed to fans. The existence of at least 245 different live recorded versions of Vysotsky’s song “I Don’t Love” gives a sense for the scale of this movement.

Why did large scale piracy start in the Soviet Union?

First, the Soviets were the first to censor music at a massive scale. With the only record label in the country releasing mostly classical music and Revolutionary songs, people needed alternatives. Whereas in the West piracy was another way to get ahold of music people liked, in the Soviet Union, piracy was the only way to get ahold of it. And with personal music ownership taking off, it was the perfect recipe for a black market.

Second, to listen to pirated music was to take a political stand. Through most of the Soviet empire’s history, there weren’t many ways to express regime opposition, at least without getting hauled to the local KGB branch in the middle of the night. Music, therefore, emerged as a way to act in the absence of open dissent. Whether you listened to the Beatles or one of the Bards, you knew that what you were doing was subversive to a regime that sought to tightly control the thinking of its subjects. It represented a silent political stand for free speech, for liberal values and a yearning for change.

Third, the way they punished music piracy empowered its growth. The Soviets understood the role of books and imprisoned people caught with subversive literature. Un-Soviet music, though tightly controlled, did not carry with it such punishments. Sure, the most celebrated distributors would get jail time, but for most, it was confiscation, or a fine, maybe. This was was seen as tacit signaling from the regime that subversive music was not a key concern. It emboldened tapists and distributors to, well, distribute, while creating cohesion among listeners who shared the bond of committing a conspiratorial act, even if low stakes.

Setting the Foundations for Modern Piracy

By the time the USSR collapsed in 1991, pirating music had been a cultural norm for over 30 years. The new “liberal” regime attempted to import Western legal frameworks wholesale, but with little enforcement and at odds with the reality on the ground, these were summarily ignored. If anything, it was a free for all. TV channels played Western content with no permission. Movie theaters played pirated Western movies. Radio stations didn’t bother themselves with license fees or royalties.

As the pendulum swung toward a market-based system, official mainstream content began to appear too — at higher prices. But ordinary citizens weren’t having it. They were already feeling the pinch of price inflation for everyday goods. No way in hell would they pay for content if they didn’t have to: for financial reasons, yes, but also as a form of protest against the perception ofmajor foreign corporations attempting to profiteer on the backs of ordinary Russians.

So if you take a country where pirated media is easier to find than tomatoes, sprinkle in the rise of the internet, an insatiable demand for content from the Western world, little discretionary income, a bunch of unemployed youth, you end up with the perfect recipe for a piracy powerplayer.

Indeed, by the late 90s, Russia became perhaps the largest distributor of pirated content in the world. It evolved from traditional piracy (cassettes) to hosting the most popular free mp3 websites, to being the largest content distributor on peer-to-peer platforms like Napster and Kazaa, to hosting some of the largest Torrent sites, to hosting VPN and anonymizing services which are still used today to access pirated content. And Russians aren’t just distributors, but major consumers too, with a 2014 study indicating that only 2% (!) of Russians pay for downloaded content.

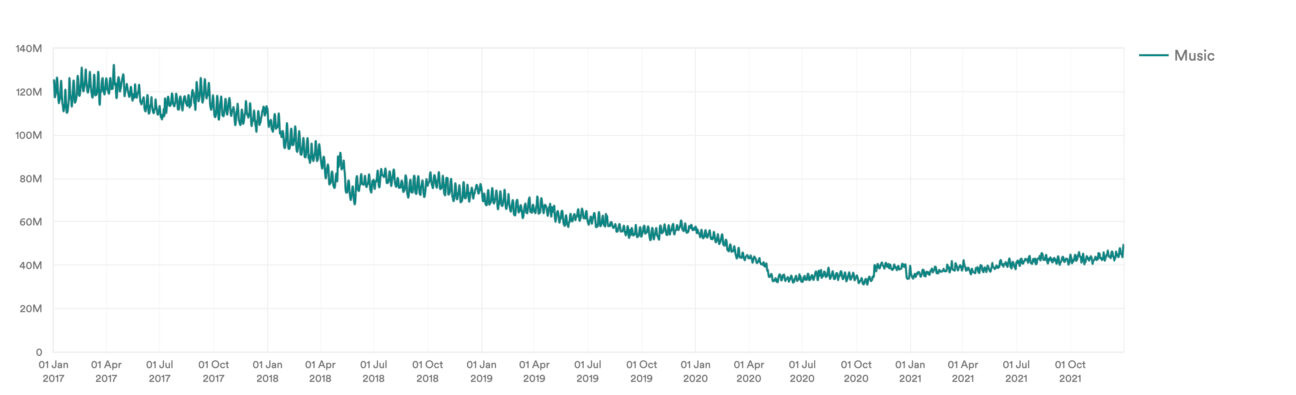

In recent years, things have slowed down though. The rise of streaming services seriously stemmed the demand for pirated content, and with it, the revenues associated with supplying it. Though Russia specific data is hard to come by, Global music piracy rates has declined over 80% in the last 5 years alone, which is pretty massive.

So perhaps it’s the end of a chapter. Or perhaps it’s just a temporary setback in the inexorable journey of ex-Soviet peoples figuring out how to make money off of media content they don’t own. We’ll have to wait and see.