Can We Use The Lottery Mindset for Good?

A look at the lottery, its history and its creative applications

In the Mexican town of Izamal, on a small road that looks as if it barely survived the Bombing of Dresden, is a tiny Loteria. The store itself is not much wider than the heavyset man who stands in its doorway. On the wall beside the entrance are fading, hand-painted letters:

Loteria Nacional

Para la Asistencia Pública.

In other (more English) words, the official name of Mexico’s Lottery is National Lottery for Public Assistance. Surprising, perhaps, but this wasn’t the first time I was seeing this.

I found the emphasis on the lottery’s role as a force for social good repeated throughout my travels in the last few months. I saw it on a highway in upstate New York. A lunch spot in Navajo Nation, New Mexico. A community center in Israel. Once you notice how remarkably similar lottery marketing is from place to place, you start noticing it everywhere (cf. Baader Meinhof phenomenon).

A California Lottery Billboard

This got me thinking: could the state-run lottery be a case study in governments successfully turning a popular vice into virtue?

I dug into the unexpectedly interesting history of the lottery to find out. In this article I’ll look at how the lottery in the US started out as a widely-respected civic activity, became roundly prohibited for a while, and then re-emerged as the $70 billion state monopoly it is today. I’ll also look at interesting ways that the same psychology that makes people vulnerable to the promises of the lottery can be used for good.

The History of the Lottery As A Public Service

The lottery gained popularity in Renaissance Europe, not as a way to gamble but as a public effort to raise money for churches and other government projects. It kept this form when it resurfaced on the other side of the Atlantic a few decades later.

Like the English language and the American Anthem, the British brought lotteries to America. The first one we know of took the form of an authorized drawing to support the Virginia Company’s Jamestown settlement in 1612.

From there, all American colonies had public lotteries at one point or another, using them usually to finance public projects: pave roads, construct bridges and wharves, build universities. In fact, Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Columbia were all built partly using proceeds from public lotteries.

But it was different from today’s lotteries in one fundamental way. In their book, Selling Hope, Clotfelter and Cook write that “the sponsors of lottery schemes volunteered their time to raise money just as prominent citizens do today for charity”. Because of this, early lotteries had practically no operating costs, while also awarding a substantially higher portion of the monies paid in prizes (usually around 85% vs. 50-70% today).

Here’s the interesting part though: because lottery revenue often replaced tax revenue (to which the colonists were strongly averse), playing in the lottery came to be considered a virtue in itself. In 1892, A. R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress, wrote:

[The lottery was] not regarded at all as a kind of gambling; the most reputable citizens were engaged in these lotteries. . . It was looked upon as a kind of voluntary tax.

The Road to Prohibition

As the American colonies grew, the scope of public projects increased and so did the revenue needed to fund them. This meant lottery operations had to increase in size. To tackle the complexity and growing geographic reach of these larger lotteries, private, for-profit organizations took on the task of running them starting in the early 1800s.

As private businesses began running lotteries, two things happened: first, through more aggressive marketing and gaming innovation, they got more people hooked on the lottery. Second, since it was difficult to control the prize payouts, fraud grew rife.

This was happening in parallel to a broader reform movement in the mid 19th century, which included the abolition of slavery and women’s rights. Gambling, then, began to be perceived as a social scourge that destroyed the fabric of society as well as the lives of the men who wove it. State by state, lotteries were outlawed. By 1878, the only legal lottery in the country was in Louisiana, and by 1890, it was gone too.

Sort of.

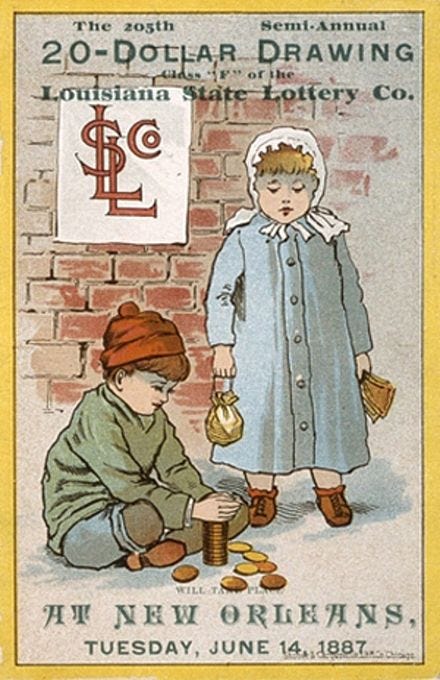

I’ll be honest, I’m not sure what’s going on in this poster.

Gambling During the Prohibition

Although lotteries were no longer technically legal at the turn of the century, this didn’t stop Americans from participating. In 1934, A full 13% of Americans reported buying illegal lottery tickets.

There were a couple of popular ways to get around the prohibition. One was to participate in foreign lotteries by snail mail (ie, the original VPN). A famous one was the Irish Sweepstakes, which seems to have been a pretty big deal and paid out major cash prizes. The lottery itself was kind of weird — you’d pay for a ticket which was assigned to a horse, and you would win if your horse won… but you couldn’t pick the horse.

Another way was for organizers to give out tickets allegedly for free (thus making it not technically a lottery) but have the prize drawing take place at an event that did require tickets. On “Bank Night”, for instance, movie theaters would swell up because a prize drawing would be held before the movie. Although anyone could participate for free, winners would have to pick up the prize within minutes inside the movie theater, so you’d de facto have to buy a ticket to participate.

Throughout the prohibition, particularly during the Great Depression, people pushed for legalization of lotteries to fund projects for the common good, like unemployment relief. A group of New York philanthropists started the National Conference for Legalizing Lotteries to support the enactment of state and federal lotteries to fund hospitals and other charitable causes. Public approval was usually high, with every poll taken after 1938 showing majority support.

Legalization

With increasing public acceptance of lotteries, a rise in anti-taxation sentiment and growing budget deficits, lotteries began to be legalized once more in the 1960s. New Hampshire was the first domino to fall and over the last few decades, almost every state has turned from complete prohibition to enthusiastic promotion.

Today, lotteries are legal in 44 states. Gallup polls show that they’re are the most popular form of gambling in the U.S., with roughly half of respondents saying they purchased a lottery ticket in the past 12 months. This really adds up.

In 2014, consumers spent more than $70 billion on lottery tickets, which added up to more than what was spent on sporting events, movie tickets, books, video games and music purchases combined.

So going back to my question… is the lottery an inventive way to capitalize on a human vulnerability for the common good?

The answer, unfortunately, is no. Let’s look at why.

1. It doesn’t benefit the causes it claims to support

When legalizing lotteries, state policy-makers have been lured by the lottery’s mysterious promise to boost funding for essential programs, especially related to education, without — get this — needing to increase taxes.

In most states, the lottery was pitched as a generous benefactor swooping in to subsidize higher education, finance books and equipment, and pay for after-school programs. In expectation of the envisioned windfall, Education groups themselves lobbied for its legalization. Emblematic here is the case of Oklahoma, a state which, despite several failed attempts, ended up legalizing the lottery after an expensive pro-lottery campaign run by a large coalition of education groups.

But as you may have guessed by the name of this section, their hopes didn’t quite come to fruition. Of the 24 states that earmark lottery revenue toward education, a full 21 had education budgets that either fell or remained flat since lotteries were introduced. According to one study, states without lotteries spend a greater portion of their total budget on education than do states with lotteries.

How does this happen? When lottery money gets allocated to education, it doesn’t increase the total — it just replaces funds that were originally allocated toward it, “freeing” it up to be used elsewhere.

Gary Landry, spokesman for the Florida Education Association, put it simply:

We've been hurt by our lottery...The state has simply replaced general revenues with lottery money - at a time when enrollments are increasing. It's a big shell game.

2. It Relies On Deceptive Advertising

In the US, as elsewhere in the world, the government is the only entity allowed to run lotteries. The lottery operation, though, is run as a profit-maximizing business. As lotteries have become increasingly lucrative sources of dollar bills, “lottery states have become more than mere providers of lottery games; they have become advocates for them, actively trying to persuade players to spend more money more often”, per a recent academic paper.

According to New Jersey's lottery director, the purpose of lottery advertising is to “take an infrequent user and [try] to convert him into a more frequent user”. This would have seemed normal for a business except that... lotteries are classified as state entities, which exempts them from federal truth-in-advertising laws.

This leads to misleading taglines like:

New York Lottery. Everybody wins.

Hmm. That doesn’t seem right. Or:

Education matters to Oregonians. That’s why $5bn in lottery dollars have gone to support public education.

Which makes it seem like Oregon’s education budget was bolstered by $5bn. Which, again, no it didn’t.

Businesses would not be allowed to make such outlandish claims without at least some accountability. And the worst part is, they pray on those who can least afford it and most need the disingenuous hope it promises. This billboard in one of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods brings the point home:

How to go from Washington Boulevard to Easy Street? Play the Illinois State Lottery.

Which leads me to...

3. It’s a Highly Regressive Tax

Per the National Gambling Impact Study Commission’s Final Report, lotteries are regressive, meaning they’re a cost that disproportionately impacts the worse off both in absolute terms and as a percent of income. The lead researcher didn’t mince words when he said, “it’s astonishingly regressive. The tax that is built into the lottery is the most regressive tax we know.”

Beyond that, there’s also a literal tax that’s hidden in the price. Because lotteries mandate that a certain portion of revenues be transferred to state coffers, it constitutes an implicit but very real tax that, unlike all other taxes including those on alcohol and tobacco, isn’t reflected on receipts and hovers around 45%.

Criticism of lotteries often takes aim at the players themselves, not the system that reinforces them. Thus America’s 85 million weekly players are labeled irresponsible, irrational actors who rely on a magical belief that they’ll overcome impossible odds to secure the life of their dreams.

But the real magical thinking underlies the system itself: elected officials and voters who believe that state revenues can increase without raising taxes or making any real sacrifices. And the worst part: once States begin depending on this revenue, it becomes really hard to undo.

Gambling as a Virtue

It’s pretty clear that the way lotteries are structured in the US (though also abroad from what I could glean) is not a good example of turning vice to virtue.

But, given the sheer size of the industry, we also know there’s something extremely compelling and habit-forming about lotteries. So I wondered: are there ways to leverage the psychology behind it for good?

Underlying the popularity of the lottery seem to be a few cognitive biases:

The Availability Heuristic, which says we tend to make decisions based on information that’s most available to us, like a recent news segment on the lucky winner of the Powerball, rather than millions of unhappy people who didn’t win.

The Overconfidence Effect, which says people tend to be overconfident in their ability to provide the right answer compared to the objective odds. In other words, we tend to think we are each uniquely positioned to pick the winning numbers (unlike all those other schmucks who clearly have no idea what they’re doing).

Regret Aversion, which is when people fear their decision will turn out to be wrong in hindsight, and they’ll regret it. That’s what slogans like the NY Lottery’s “Hey, You Never Know” are capitalizing on. (tangent: Pete Holmes’ 3 minute standup on that tagline)

Present Bias Preference, which is our tendency to choose a smaller reward today (dopamine hit from a lottery ticket) than a potentially bigger reward in the future (having savings in retirement)

I can think of two frameworks to capitalize on these biases to promote healthy behavior:

You can reward good behavior by offering a prize paid for by a third party whose interests are aligned with that of the individual

You can reward good behavior by fining the behavior you’re trying to discourage

Below we’ll look at how these frameworks can (and sometimes are) being applied in the real world.

Money & Finance

Encouraging People To Save More

The oldest and best known application of lottery biases is in increasing people’s savings rates. A recent report by the Fed found that 24% of American households didn’t have $400 in easily accessible money. That’s not because 75 million people are so poor -- it’s because we aren’t great at saving as a society. Beyond helping the individual, saving helps banks by giving them liquidity they can then use to finance mortgages and business loans.

Already in the 1600s, British banks came up with ‘prize-linked savings’ to capitalize on the lottery mindset which was growing in popularity. It worked by using the interest to buy ‘tickets’ for a monthly jackpot. The more you put away, the more likely you are to win, up to a certain amount.

This practice was brought back to life in Britain in 1956 and proved hugely successful. At the program’s 50th anniversary, Britons held £32 billion in bonds, providing the government with capital at a rate cheaper than borrowing. Participation is extensive: nearly 40 percent of Britain’s population hold Premium Bonds today.

Getting Businesses To Pay Their Taxes

In the 1950s Taiwan faced a serious problem. Businesses avoided reporting their income by not issuing receipts and taking only cash, making it impossible to tax. The government took a creative approach: it provided businesses with special machines for printing receipts that doubled as lottery tickets. They then advertised the lottery to the general public. People started asking businesses for receipts to be eligible for the frequent drawings, forcing them record sales.

In the first year alone, the bi-monthly lottery led to a 75% increase in tax revenue. Many countries, from Brazil to Slovakia, have since implemented similar systems.

Healthcare

Even more so than saving money, there are a bunch of parties who have a stake in promoting healthcare beyond the individuals themselves. This includes governments (whose GDP increases and healthcare expenses decrease with a healthier population), insurance companies (who have to pay out less in premiums) and corporations (who benefit from a more productive workforce).

Safe Sex

Researches in Lesotho set up a lottery to promote safe sex practices. They tested the participants every four months for two STIs correlated with HIV. Testing negative entered them into a lottery to win about a week’s worth of salary. The results were pretty astounding: researchers found a 21.4% decrease in the rate of HIV infections in the treatment group after two years.

One wonders whether designing lottery-based experiments targeted at an audience undeterred by one type of risk (in this case, sexual) can increase the likelihood of them responding positively to an approach predicated on another type of risk (ie, financial).

Appointment No Shows

To address this major issue for medical providers, a clinic set up a lottery. When patients checked out and made their follow-up appointment, they were invited to play a Spinning Wheel game. A prize was certain, but they didn’t know if they’d won a $10, $50 or $150 gift card. To find out and receive their prize, they had to keep their appointment. The no-show rate dropped to below 30 percent.

Other Fun Ideas

Insurance

Insurance itself is kind of like a reverse lottery: people pay into the system so that if they get “picked” (eg. something catastrophic happens), they get a payout. It’s in the interest of insurers to minimize payouts -- ideally not by swindling payors through executing linguistic acrobatics in the fine print -- but by encouraging preventative practices.

Some, like Oscar with their step challenge, are starting to think about it, but the field is very much in its infancy. You can easily imagine weekly or monthly sweepstakes for relatively small amounts ($50, $100) entered into by people following simple behavior best-practices. Now is the perfect time because it’s never been easier to leverage the recent advances in digital therapeutics to deliver both the encouragement and the tracking mechanisms.

This can be applied to weight-loss programs, populations with chronic health conditions, even basic nutrition and exercise. It can even be relevant to car insurers, who can enter drivers into a small sweepstake every time they buckle their belt using very basic IoT. And the fact that lower-income earners are more susceptible to lottery-based incentives and tend to be more adversely impacted by lifestyle-based diseases and adversities makes this all the more helpful.

No Loss Lottery

There are no free lunches right? Well, sort of.

Another fun idea is to collect funds up front from a large pool of people, make the payout be the interest earned on the large pool of collected funds and award that to the lucky winner. Everybody else gets their initial buy-in back (just sans interest). A blockchain startup called PoolTogether is actually implementing something similar, which is pretty cool.

It seems like once we are able to effectively ‘code’ money, as crypto promises, we can actually run this at scale, especially in communities with low savings rates, with only upside to participants.

Speed Camera Lottery

I will close out with a personal favorite: a really simple, elegant concept. Here, cars that pass through a certain intersection below the legal speed limit get entered into a lottery to win a cash prize paid for by fines collected from those who speed. In an experiment run in Sweden, researchers found the average speed decreased from 32 to 25 km/h which, according to their calculations would cut down fatal accidents by 32%. Pretty cool.

I started this little adventure three-thousand words ago with the naive belief that state-run lotteries might be an interesting case study in leveraging human biases for the common good. Although it may have started out that way, it’s certainly not true today. The lottery is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, a predatory and ineffective institution that tries to pass itself as an ally to the (mostly poor) communities it preys on.

But I also found that the same cognitive biases that make us susceptible to its promises can be used to improve our lives. This is especially true where the interests of individuals are aligned with stakeholders in whose financial interest it would be to finance the prize. Insurers, governments, corporations, startups -- take heed.

It makes me wonder: what would the world look like if we started ‘exploiting’ human biases for good?