The Optimistic Case for the Future of Mental Health

How a pandemic, and instagram influencers, are forcing us to rethink things

Hi,

This is Gil, from the Damn Optimist. Below we will:

Look at COVID’s immediate impact on mental health stigma and reform

Explore some intersecting pre-COVID social trends that have been driving positive change

But before we dive in: optimism can be a really effective tool to avoid feeling sadness or grief. That’s a problem because grieving when people suffer is necessary and worthwhile.

So it is with COVID. I am optimistic that the pandemic will force us to make structural changes that are long overdue. But that does not take away from the tragedy of its large-scale destruction. The challenge for any optimist is to stay viscerally conscious and respectful of ongoing suffering while imagining a better tomorrow.

The Pandemic and Mental Health

The pandemic we’re facing sucks not only because it attacks our bodies, but because it destroys our minds. Current models predict that in the US alone, 75,000 people will die from COVID-related mental health issues. Rates of substance abuse, domestic violence and neglect, and abuse of children are all up. The CDC highlights these issues on it’s home page, explaining that the psychological impacts of the pandemic — difficulty sleeping, changes in eating patterns, increased use of tobacco and alcohol — also reinforce the severity of the disease itself, once it strikes.

“We simply were not made to operate in this way, with so much uncertainty” says Cheryl Carmin, PhD, a psychology professor. “The brain loves routine, knowing what’s coming next, and familiarity. To be thrown into the opposite of that, so quickly, is causing quite a lot of anxiety, fear, and stress”.

So how exactly can any good come from it?

A few ways:

1. By bringing mental health into the national conversation

No one is beyond the pandemic’s deadly grasp. Every one of us is trying to manage working from home or searching for work while balancing the needs of relatives, partners and friends and, often, dealing with illness or grief. Nearly half of Americans report that the pandemic is impacting their mental health. Nearly half. 34% report symptoms of anxiety or depression.

This sh*t’s HARD. It impacts all of us. And that’s exactly the point. When half of the population openly reports that the pandemic is messing with their heads, it becomes much easier to talk about it. We are more likely to be met with empathy within our social circles and communities. When we become more willing to talk about it, our overall level of literacy about mental health goes up, together with it’s ranking on the list of priorities we collectively need to address.

It’s clear that the pandemic is prompting national conversations that are long overdue. Academic op-eds, journal articles, NYT opinion pieces, the news, Reddit threads, LinkedIn posts, are all covering variations of the same questions: what should public health policymakers be doing about mental health? What should individuals be doing? Where do healthcare providers fit in? Do employers have an obligation to help?

This is how change starts: many people, across different spheres, asking questions. Employees of their employers, constituents of their elected officials, journalists of their editors, aunts on Facebook timelines.

Pre-COVID, healthcare institutions, researchers, writers and journalists have been toying with the resolution of the microscope we use to explore mental health as a theme, it’s importance coming into somewhat clearer view over time. COVID, by bringing the issue into sharp relief on a global scale, is cleaning our collective lens. It’s giving us a common language to start discussing the questions that previously were relegated to the fringes of the national conversation.

2. By forcing employers to address it

The seismic mental health tide is also forcing employers to act. Our teams and managers see us sans culottes — rocking old t-shirts, beds unmade, partners chasing ice-cream-stained children in the background (or is that just me?). Absent a separation of home and office, our employers learn more about us than ever before.

BBC Dad & OG work-from-home trailblazer

Our coworkers and bosses are likely also feeling the psychological impacts of the pandemic, and there’s nothing like feeling someone else’s pain to catalyze change.

And so, changes are afoot. Employers are extending work from home timelines, or taking more flexible approaches to it. In response to the pandemic, almost half of surveyed employers are offering vulnerability or discussion groups for mental health; 69% provide access to virtual therapy. One third of employers are offering support for sleep and the more progressive are offering mental health days. 78% of employers have programs dedicated to improving work-life balance.

COVID, it seems, accelerated an important shift. Whereas before, caring about employee mental health was the reserve of high-paying startups competing for top talent, it is slowly becoming table stakes for many employers. The American Psychological Association is stepping up it’s expectations of employers, cities are rolling out initiatives to help a wide variety of employers offer better mental health coverage, and HR journals targeted at executives applaud the rapid employer mobilization in this space — while demanding more. Even though some companies are merely gesticulating, they are doing it because they realize that expectations are beginning to change, and employers are expected to care for the mental wellbeing of their workforce more than they ever have in history. That’s a step in the right direction.

3. By forcing long overdue regulations

Although the country’s leader is a disgruntled cheeto with an embarrassing leadership team, US institutions like the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the FDA and the Department of Health, as well as state-level agencies, still have highly competent people devising and implementing policy. These functionaries and legislators enacted a flurry of regulatory changes that eased access to quality care and made it more affordable while reducing administrative burden.

The Families First Coronavirus Response act guaranteed paid sick leave for people with COVID-19 symptoms or those caring for sick family members. That’s extensive coverage and, for a country with the lowest mandated vacation days in the world (a solid zero), is pretty meaningful.

There’s new funding, too. The CARES act, signed into law in March, allocated $425 million toward the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and an additional $4 billion for community health centers. These moves were praised by the American Psychiatry Association and the money will be funneled into essential services like suicide prevention, community care and expansion of social service staffing. And while the money is significant in its own right, it’s further encouraging that expanded mental health support was in the very first batch of federal bills signed to fight COVID.

There were also more tactical but no less important regulatory changes. The Center for Medicaid and Medicare Service waived copays for telehealth services rendered in “all areas of the country in all settings”, and promised to reimburse providers for all services provided via telehealth as if they were in-person. This was a huge boon for providers and patients alike, with telehealth proving an essential tool in expanding access to care and reducing its costs.

There were moves to better support those fighting substance abuse, like increasing the maximum take-home dose of methadone and the waiving of the need for in-person prescriptions of buprenorphine, both treatments for drug addiction. Providers also don’t have to be licensed in the patient’s state to prescribe these.

Finally, a number of state governments are increasing access to intermediate care options. Pre-COVID, services were clustered around two ends of the mental health spectrum: loose outpatient care, like seeing a therapist, or intensive inpatient treatment, like admission to a psychiatric ward. Since the rise of COVID, several states (like New York) have encouraged the rise of intermediate care such as intensive outpatient programs and partial hospital programs, which serve as middle ground between the two extremes.

The equal reimbursement for telehealth and the waiving of state-restrictive regs has dramatically increased supply — and thus access to care — while keeping down costs for providers and patients alike. States are financing alternative mental health treatments thus increasing the likelihood people will find something that works for them. Those battling substance abuse have more flexible ways to access treatment medications. Still — we are underprepared for the psychiatric fallout of the pandemic. But if even some of these regulations rollover into the post-COVID future, they will shape a more accessible and affordable mental healthcare landscape for future generations.

4. Virtual care for mental health… at scale

COVID forced federal and state agencies to not only incentivize telehealth (see #3), but also to re-assess the restrictive data, privacy and insurance policies which have thwarted its growth thus far.

With these changes in place, the rise of telehealth has been the talk of the town in the healthcare world. Although we’ve had the technology to transition care to virtual modalities for a while, providers, payors and patients did not have strong incentives to adopt it. Mental health practitioners in particular were skeptical of the ‘cold’ interaction of telehealth vs. ‘warm’ work in person. The fact that many studies showed outcomes from telehealth were the same as from in-person work did little to sway providers.

Until now.

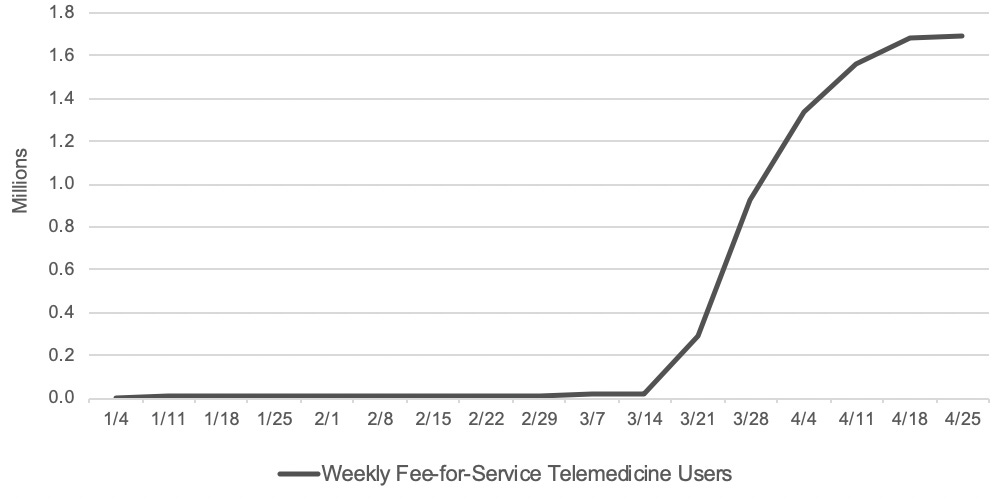

Not only did general adoption triple since the beginning of the pandemic...

… but penetration among older people and those with disabilities, who many feared would be left behind in a broad shift to virtual care, has been staggering: Medicare recipients went from 13,000 visits per week to 1.7 million in the last week of April. At peak, 43.5% of all visits were virtual, up from 0.1% just 90 days earlier.

Similarly, many mental health facilities have switched their care from in-person to virtual, especially for things that really should have been virtual in the first place, like medication management, case management, peer support and wellness checks. This is good news because it reduces barriers to entry, lowers costs all around and makes follow ups more efficient (and therefore more likely to happen). It’s also a great opportunity for clinicians, including psychiatrists and behavioral health specialists, to develop a “webside” manner en masse and for patients to get familiar with it, both of which are table stakes for virtual behavioral telehealth to be viable long-term.

In line with this shift, we’ve seen order of magnitude increases in usage of virtual therapy platforms. Talkspace, a leader in the space reported 65% MoM usage jumps since March. Rival Ginger saw a 50% jump in usage from February to March while AbleTo reported 25% week over week increases over the same period. Therapists are getting swayed too — many have said they will continue online therapy post pandemic — and patients give it consistently high ratings. The pandemic, by forcing online the delivery of mental health services, opened the eyes of both users and providers to the potential for telemedicine to deliver high quality mental care that’s affordable and easily accessible. Even as we reopen and shift some of the digital interactions back to in-person care, this is a long-term force that’s here to stay.

These changes are built on the tailwinds of a few positive social forces

The COVID-driven changes above are built on a few important, positive trends that accompanied the rise of the digital era.

What? Aren’t we facing the worst global mental health crisis, like, ever?

Today’s global mental health epidemic is not unprecedented. Yes, more people have anxiety and depression than ever before… but that’s because we have way more people than ever before. Adjusting the data for growth in population shows that the rate of mental health issues was roughly the same in 2017 as it was in 1990. But we also have much less stigma and therefore much more self-reporting today, which means past data was underreported. This suggests we’re doing better today than in previous decades, when people were ashamed to admit to having mental health issues.

And because people are talking about mental health more, it can create the perception of a unique and unprecedented challenge. But the truth is that the first two decades of the twentieth century set in motion long term trends which laid the foundation for the real improvements in mental healthcare we will see in the 2020s.

Look: the problem with mental health in the US is very real. The lack of sufficient care is very real. But as we (justly) demand more of our health systems, of our insurers, of our employers, and of each other, we should also recognize the momentum we’re gaining. Instead of robbing the cause of its urgency — as some may fear — I believe this is important in building confidence that change can be achieved, and even in relatively short timeframes, which is incredibly empowering.

It is now more acceptable to struggle with mental health, and to seek help for it, than it has ever been in the history of humanity. Today, a majority of college-aged adults view seeing a mental health professional as a sign of strength. People’s willingness to work, live and continue a relationship with someone with mental health issues has increased by 11% in the last decade alone, while 87% of Americans now agree that having a mental health disorder is nothing to be ashamed of. A full 86% believe mental health issues can get better. And, in the face of the increasing suicide rate, the vast majority of Americans agree that people who are suicidal can be treated and live full, happy lives (91%), indicating a mainstream recognition of the importance and value of clinical care.

Why are you optimistic?

There are a few interesting, intersecting trends:

Interest-based communities and globalization of knowledge

New funding

Gen Zs and Influencers are rebranding vulnerability

The rise of Value-Based Care

1. The rise of interest-based communities and the globalization of knowledge

Among the internet’s superpowers, two stand out: the growth of online communities and the scaling of knowledge. For the first time in history, humans were able to create and participate in groups built around specific topics and interests that were geographically agnostic and therefore truly global. Almost from the start, the long tail here was really long, so one could find almost any affinity-based community online, no matter how obscure. And of course, the internet proffered practically infinite knowledge, free of charge.

There are serious downsides to these superpowers, like the rise of extremist communities and self-diagnosing toe aches as cancer. But covered by the internet’s cloak of anonymity, the digital world empowered users to both seek out knowledge about their mental health issues, and participate in communities where this knowledge is shared and discussed.

A perfect example is Reddit’s r/depression, a 700k-strong subforum to discuss — you guessed it — civil engineering. Just kidding. Depression. It’s tagline is ‘because nobody should be alone in a dark place’. And despite occasional toxic behavior, it is generally a constructive place to share struggles, post progress, discuss loneliness, build empathy, and support others. Indeed, a language-analysis study from the University of Utah showed that users who engaged with r/depression demonstrated improvements in 9 out of 10 linguistic dimensions such as ‘anxiety’, ‘negative emotion’, ‘anger’ and ‘sadness’ over time.

And while Reddit forums represent the traditional format of online communities, these communities are being re-invented for Gen Z too. WANA is a mobile-first community specifically for people with various chronic issues, including anxiety and depression, to connect, form support groups and share resources. Kinde bills itself as the social network for mental health. In all, there are at least 48 funded companies specifically in the peer-to-peer mental health support space.

2. More (VC) money than ever

Speaking of companies, a recent tally showed that there are now over 1000 VC-backed mental health startups. From hardware that helps sleep (kokoon) to general mental wellbeing (happify) to using VR to treat anxiety (Psylaris) to B2B tools that power behavior health clinics (like TheraNest), it really feels like the sky’s the limit. As one investor in the space put it:

“The time is now for someone to dedicate funding to early-stage mental health founders as stigma and other limiting factors have drastically declined and paved the way for an influx of ideas, talent, and businesses in this space.” — Stephen Hays

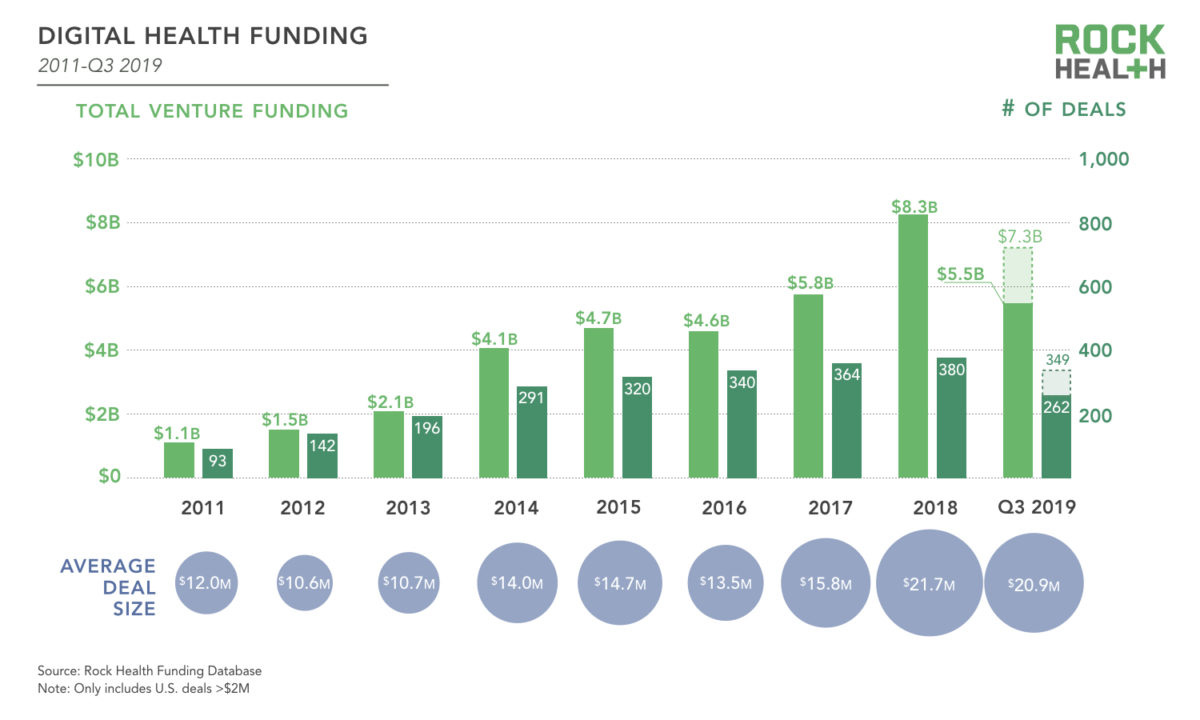

Total funding has 7x’d since 2011 alone

The industry is turning it’s problem-solving hivemind to mental health in earnest, having raised almost $5 billion in funding for startups over the last few years and made it the next “cool” problem to work on. And where money flows, so do really smart people looking to solve hard problems.

A small sample of the 1000+ mental health startups active today (h/t WhatIf Ventures)

3. Celebrities and Gen Z made it cool to talk about mental health

Content that gets applauded gets created. Prior to the rise of social media, when publicists carefully curated what public figures shared with the world, displays of vulnerability were rare. Even then, they usually had its form (tears, juicy facts) but rarely its content (sharing stigmatized feelings like shame, fear, anger).

With the rise of social media, we have, collectively, normalized and encouraged oversharing — play by play documentation of lives, starting with the public figures and influencers we look up to. The need to keep up an airbrushed public identity clashed with the pressure to share frequently leading, for some, to breakdowns of the public image. Often this came with more literal breakdowns, admissions of imperfection, heartfelt confessions that their lives aren’t perfect, and what they’re dealing with and losing sleep over — all posted for the world to see.

Whereas the ruling paradigm in the pre-instagram era was that shows of vulnerability would take away from the perfection that people in the public eye seek to project, the reaction to these displays of inner truth told a different story. These displays made public figures more real, and thus more relatable to followers. It also rewarded shares that dug below the psychological surface with plenty of likes and comments. Over time, this process normalized public sharing of real feelings.

And you can’t normalize the sharing of feelings without talking about mental health. It has become not only permissible but encouraged for cultural influencers to reveal their struggles with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, bipolar disorders and more. This trend has rippled out from the Emma Stones and Reese Witherspoons, the Kanyes, the Keshas and Lady Gagas, the Jenners and the Kardashians, the Biebers and the (nee) Baldwins to ordinary people, because that’s how cultural influence works. And even if the vulnerability is in search of social engagement or, as cynics charge, profit, it doesn’t actually matter because it means young people are growing up seeing it is okay to struggle and openly discuss mental health.

This dovetails well with Millennial/Gen Z’s high expectations for transparency and authenticity — of their influencers, their brands and their elected officials (which I wrote about here). Taken together, we are seeing a seismic change in attitudes toward mental illness. Social stigma has been the biggest challenge to improving our overall mental wellbeing and it makes me optimistic to see the veil — if slowly — being lifted.

4. The Growing popularity of Value-Based Care

Oak Street’s huge IPO earlier this month may have gone unnoticed because it was the same day some guy in the White House proudly signed an executive order to ban TikTok. But for healthcare industry observers, it was a fundamental vote of confidence in a new(ish) healthcare model. Where traditional healthcare providers are paid on a Fee-For-Service basis (the more you do, the more you get paid), there are new kids on the block who are blazing an innovative trail using a different model: Value-Based Care. Under this framework, providers are incentivized to improve overall health outcomes while reducing, not increasing, costs of care by sharing any medical care cost savings with healthcare plans.

Organizations like Oak Street and Cityblock Health (my own employer) are doing this by bringing an integrated model that combines medical, behavioral and social care with a specific focus on prevention, not reaction. They have therapists, psychiatrists and behavioral health specialists on teams that consult with a person’s dedicated doctors and nurses to create holistic treatment plans based on the wide breadth of evidence showing that mental and physical health are interdependent. In this new model, addressing underlying mental health issues early is an essential strategy for reducing cost of care and improving patient outcomes.

This approach is bearing fruit. In it’s SEC filing, Oak Street reported a 51% reduction in hospital admissions, 42% reduction in 30-day readmission… while maintaining some of the highest patient satisfaction scores in the healthcare space. In an industry that’s painfully slow to change, Value-based Care is rapidly gaining momentum, which bodes well for a care model that incentivizes and prioritizes mental health.

There’s no denying.

We are a deeply ill society. One in four Americans experiences mental health issues every year, but only half of them get the care they need. Suicides have been steadily rising across the board. Mental health programs are understaffed and underfunded. We’ve got a LOT of work ahead of us.

The macro trends, though, give reason for cautious optimism. Over the last two decades, we have seen a huge jump in funding for mental health innovation, the rise of new care models focused on behavioral health, increasing acceptance of vulnerability and discussion of mental illness, and the rise of online communities to exchange knowledge and share struggles.

There is no way around the fact that COVID will have devastating consequences on our collective mental health. But it has also served as a systemic shock that is forcing us to candidly re-examine our status quo and make difficult changes. With the positive momentum of the early 21st century, I am hopeful that our jagged path, alternating between crisis and discovery, is leading us to happier, healthier lives.